ABSTRACT:

It is essential that people are informed about the particularities related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, it is important to be aware of the risks related to SARS CoV2 infections in pediatric patients. In this article, you will find current evidence from scientific publications chronologically. With this information, the goal is to raise awareness about the pandemic, prevent, and save lives.

Here, it will be explained why Pediatric Multisystemic Inflammatory Syndrome is directly related to coronavirus. Epidemiological tests were carried out in Wuhan in January to document the progress of different pediatric patients. Analysis of the results showed that infants under one year of age were at significant risk of developing a more serious disease when compared to adolescents.

Another study also carried out in Wuhan, made it possible to understand that pediatric patients, even with mild symptoms, still put adults at risk of infection (especially those with pre-existing conditions). In addition, successful results of a study conducted in Italy will be addressed. In this context, it is important to mention that it is essential to evaluate studies individually so that the analysis is accurate and not just mere speculation.

Likewise, in order to understand pediatric infectious diseases caused by the virus, illustrative cases such as the pediatric Children’s Hospital Montefiore in New York, the Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús in Madrid, and the panorama in Latin America are going to be analyzed.

BACKGROUND AND STATISTICS

In this article, we will talk about the risks related to infections of CoV2 SARs in pediatric patients. In a chronological way, we will take into account current evidence from scientific publications. Analyzing these issues does not pretend to generate an alarm state; the goal is to create awareness and to prevent and save lives during this pandemic.

The pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome is directly related to the SARS-COV-2 virus, better known as coronavirus, which has put our immune systems under testing.

There are many publications on the impact of exposure to the virus and its health implications.

For instance, on January 12, the health authorities in Wuhan, China published the results about research concerning viral genetic material. With this information, they were able to carry out epidemiological tests between January 16 and February 8, which made it possible to document the progress of patients under 19 years old.

However, only about ⅓ of the 2,135 reported cases were diagnosed with positive PCR results, and the remaining ⅔ were diagnosed based on their symptoms, in addition to a history of exposure to the virus (1).

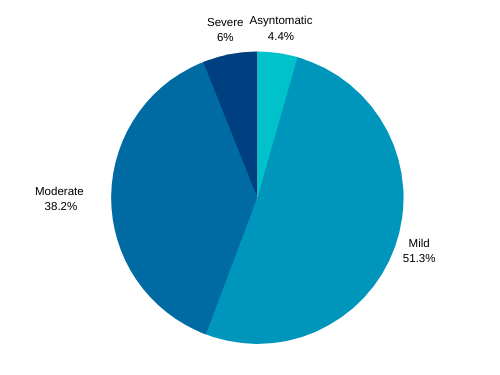

This report indicated that 4.4% of the patients were asymptomatic, 51% of the patients presented a mild condition, 38% of the patients presented moderate severity, and 6% of the patients had a severe or critical condition (2).

Report with statistical data on patients in China.

Patients who were characterized as “mild condition patients” presented very similar symptoms than patients with common flu. These patients presented evidence of a pulmonary infectious process in studies such as X-rays or computed tomography. Patients under a severe condition received some kind of life support including oxygen therapy.

This article, previously presented by the China Infection Control Center, was published in the American Pediatric Association. When contrasting the evidence in adult patients, the proportion of children affected by the virus was significantly lower.

However, in the analysis of these results, it was possible to see that infants under one year had a much more significant risk of contracting a more serious disease when compared to adolescents.

Later on, in a publication based on 171 pediatric patients, also from Wuhan, the clinical scenario of infection very similar to seasonal, or winter, seasonal influenza in the United States was confirmed (3). This study was published by the New England Journal of Medicine on March 18. The study helped to understand that even if the pediatric patients only presented mild symptoms they could put adult patients at risk of contagion, particularly those with known risks of severe infectious status like diabetic patients, or patients with other preexisting conditions.

Also, Italy obtained successful results: only 1% of its positive tests were from patients under 19.

Again, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of about 100 pediatric patients with positive PCR results, between March 3rd to 27th, where the average age was 3 years old, and the source of exposure of these children was of about 55% and it occurred outside the family nucleus, or from an unknown source (4). In the distribution, 21% of these patients were asymptomatic, 58% presented a mild condition, 19% presented a moderate condition, 1% had a severe condition, and the remaining 1% presented a critical condition.

| Study | Asymptomatic | Mild Conditions | Moderate Conditions | Severe | Critical Condition |

| Italy in a group of 100 kids | 21% | 58% | 19% | 1% | 1% |

| De Dong et AL. | 4.4% | 51% | 38% | 6% | |

Report with statistical data on patients in Italy.

In this case, the difference was that the criteria for considering a patient’s case as severe versus considering it as a moderate case was based on the findings of auscultation with a stethoscope. So, these percentages were limited to the capacity of the doctors on being able to hear some changes in the normal sounds of the patient’s breathing. This scenario creates a possible disproportion in the criteria used in this study, compared to the study carried out by the Chinese authorities. For this reason, each study must be evaluated individually, and we cannot draw any conclusions that do not constitute mere speculation.

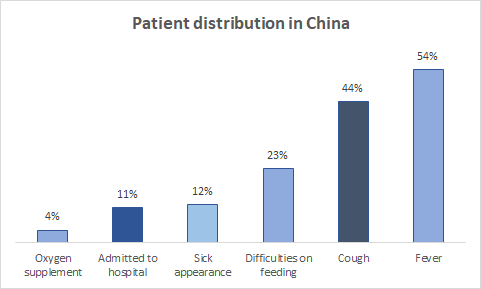

Out of 100% of these patients in Italy, 54% developed fever, 40% had more than one symptom, 23% presented difficulties on feeding. Under the opinion of pediatricians, 12% had a physical sick appearance of a higher degree of illness, 11% were hospitalized, and 4% required some type of oxygen supplementation, from nasal cannulas to more aggressive measures such as mechanical respiratory assistance.

| Oxygen supplement | Admitted to hospital | Sick appearance | Difficulties on feeding | Cough | Fever |

| 4% | 11% | 12% | 23% | 44% | 54% |

Table 2.

Statistical data on patients in Italy.

Report with statistical data on the distribution of patients in China.

Pediatricians around the world have been alert to possible complications in their patients. In New York, these risks became evident in April.

In this city, Children’s Hospital Montefiore of Pediatrics admitted 13 infants to its intensive care unit. Despite the deep efforts of the medical team, many kids could not stop their critical condition (at the time of the publication of their report) (5).

Likewise, in Madrid, on May 27th, the pediatric intensivists doctors at the Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús observed a very similar scenario. In their publication they alerted about patients without pre-existing conditions who were admitted to critical care due to viral infection (6).

The magazine for the Management and Practice of Public Health announced that the number of severe cases projected for the US could exceed the capacity of the health care system.

If the infections exceed only 5% of the United States child’s population, intensive care units could face more than 1000 admissions.

For this reason, parents have the task of educating their children from home, thus avoiding their exposure to the virus in classrooms (7).

CONCLUSION

In developed countries, children are at a much lower risk of health complications compared to the elderly. These communities manage to protect their infants during all stages of their infectious process; that means that with an early diagnosis, their symptoms are monitored until they are recovered.

However, the outlook for Latin America is not so encouraging due to the existing limitations prior to the COVID-19. Unfortunately the problems for minorities such as the afro community and the Latinamerican population are accentuated by the economic crisis that the pandemic has caused.

Poor access to basic health services in our region are among the most critical limitations for the care and management of these patients. This inequality is higher when parents lose their daily livelihood because they are forced to close their small businesses, or when they have lost their jobs. All of this could cause limitations and problems in their food security, not to mention those families who also have lost their homes.

We have to join our efforts as a responsible society, so that each family can ensure the well-being of their children without putting others at risk, while reinventing themselves and exploring new alternatives to bring sustenance to their homes. We urge you to provide alternatives for your community, and to promote health since access to it is everyone’s right. You can make the difference!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Dong, Y., Mo, X., Hu, Y., Qi, X., Jiang, F., Jiang, Z., & Tong, S. (2020). Epidemiological Characteristics of 2143 Pediatric Patients With 2019 Coronavirus Disease in China. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

- Dong, Y., Mo, X., Hu, Y., Qi, X., Jiang, F., Jiang, Z., & Tong, S. (2020).

- Epidemiology of COVID-19 Among Children in China. Pediatrics, 145(6), e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

- Cai, J., Xu, J., Lin, D., Yang, Z., Xu, L., Qu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Jia, R., Liu, P., Wang, X., Ge, Y., Xia, A., Tian, H., Chang, H., Wang, C., Li, J., Wang, J., & Zeng, M. (2020). A Case Series of children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection: clinical and epidemiological features. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 145(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa198

- Lenge, M. (2020). Correspondence Children with Covid-19 in Pediatric Emergency Departments in Italy. Nejm, 1–4.

- Chao, J. Y., Derespina, K. R., Herold, B. C., Goldman, D. L., Aldrich, M., Weingarten, J., Ushay, H. M., Cabana, M. D., & Medar, S. S. (2020). Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Hospitalized and Critically Ill Children and Adolescents with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a Tertiary Care Medical Center in New York City. The Journal of Pediatrics, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006

- García-Salido, A., Leoz-Gordillo, I., Martínez de Azagra-Garde, A., Nieto-Moro, M., Iglesias-Bouzas, M. I., García-Teresa, M. Á., Cabrero-Hernández, M., De Lama Caro-Patón, G., Gochi Valdovinos, A., González-Brabin, A., & Serrano-González, A. (2020). Children in Critical Care Due to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: Experience in a Spanish Hospital. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine : A Journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002475

- Pathak, E. B., Salemi, J. L., Sobers, N., Menard, J., & Hambleton, I. R. (2020). COVID-19 in Children in the United States: Intensive Care Admissions, Estimated Total Infected, and Projected Numbers of Severe Pediatric Cases in 2020. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP, 00(00), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001190

Health Facts Now has the privilege of having Dr. Jhonatan Rivera-Mora as its Director of the Medical Department. He was born in Quito, Ecuador into a Christian missionary family. He completed his doctorate in Medicine at the San Juan Bautista School of Medicine in Caguas, Puerto Rico, in June 2019. In July 2019, Dr. Rivera-Mora began working for Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts as a postdoctoral researcher in the division of Endocrinology, Hypertension, and Diabetes. In this position, he also holds an appointment as a postdoctoral researcher for Harvard Medical School under the auspices of the National Institute of Health (NIH), Dr. Rivera-Mora participates in research activities for the management of diseases such as hypertension. In this scenario, Dr. Rivera-Mora shares time and knowledge with some of the most recognized scientists and doctors in the world in their respective fields.